Any creative project, or any broader body of work, needs a spine for it to stick. I am not talking about single images, for instances; photos you capture on the street or in Mother Nature that doesn’t become part of something bigger. No, I am talking about something more comprehensive, such as a photo essay, a book, a film, a concert, you know, whatever you are working with and put together to express something deeper and more profound.

The spine for such a project begins with your first strong idea. You were scratching to come up with an idea, you found one, and through the next stages of creative thinking your nurtured it into the spine of your creation. The idea is the toehold that gets you started. The spine is the statement you make to yourself outlining your intention for the work. You intent to tell this story. You intent to explore this theme. You intent to employ this structure. The audience, the viewers, the readers may infer it or not. But if you stick to your spine, the piece will work.

Let me take a photographic photographic project I have been working on for quite some years and am about to put together in its final form, as an example. You have already seen some of the photos, here in this blog that will be part of it. Already from the very beginning, I had an idea of how I wanted to pursue the project. The foundation for the project is a bunch of farm ruins that are spread over a small area in a bottom of a valley very close to my home city Bergen in Norway. Often times I have wandered around these ruins—and felt a tremendous draw by them. I can feel the harsh existence it would have been to make a living here back hundreds of years when the small farms were still inhabited. Even more so, I almost feel at home, as if I had once lived this life. Yes, this sounds high-flying and even daft, but nevertheless it’s how I feel every time I wander around in the ruins.

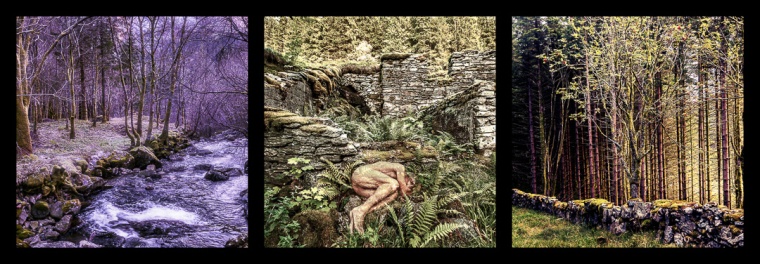

That feeling is the foundation of the photo project. Then I have nurtured the idea and elaborated how to convert that feeling into something more tangible. I wanted to pursue a threefold expression. Firstly, I want to hint at the life as it was back in the old days, the farmers’ world and how they understood it. Then I wanted to tell my own connection with this area. Finally, I want to express the beauty of the valley the farmers and myself have shared through this many hundreds of years. Only now am I putting the project together, and I have chosen the final outcome as a series of triptychs—images that consists of three panels or three separate photos put next to each other. One of the final photos is then one above. Please click it for a larger screen view.

What I have just described here is the spine of the project.

In my early days of creative fumbling and trying out, I never thought about spine. I was content to receive any random thought floating through the ether that happened to settle on me that day. I didn’t even think I needed a supporting mechanism for the photos I took, the pieces I wrote, the drawings I made. I thought getting lost was part of the adventure.

I was wrong.

Floating spineless can get you through the day, but at some point you’ll be lost in the middle of a project, whether it’s a painting, a novel, a song, a poem or a photo project, and you won’t know how to get back to what you are trying to accomplish. It might not happen in your first creation, which, in your bubble of sweet inexperience, may skim from heart to mind to canvas, page, stage or image sensor exactly as you intended, perfect in shape, proportion, and meaning. However, it will happen in the next piece, or the one after that. It happens to everyone. You’ll find yourself pacing your particular white room, asking yourself: what am I trying to say? That is the moment when you will embrace, with gratitude, the notion of spine.

You can discover the spine of a piece in many ways. You can find it with the aid of a friend. That’s what editors do for writers who have lost their way. You can induce the spine with a ritual. Sometimes the spine does double duty, both as the covert idea guiding the artist and the overt them for the audience. That’s what makes Herman Melvillle’s Moby Dick so powerful and enduring. It has a solid unrelenting spine: Get the whale. Sometimes the spine of a piece comes from the music you listen to. There are just so many ways the spine can come to you or be developed by yourself.

Keep in mind that coming up with a spine is neither a chore nor a distraction that takes you away from the real work of the creative process. It’s a tool, a gift you give yourself to make your job easier. As for the particular quality of your spine, it doesn’t matter how you developed it or how you exploit it; your choice of spine is as personal as how you pray—if you pray at all. It’s a private choice that only has to provide comfort and guidance to you. It’s your spine. Use what works for you.

Would you like to get motivating thoughts related to the act of photographing? Every once a month I write Sideways—nuggets of inspiration on photography. Sign up to receive Sideways in your email.

Photo Workshops and Tours in 2023

These are the photo workshops I and Blue Hour Photo Workshops plan for this year.

”Along the Streets of Prague”—five days in the beautiful city of Prague, The Czech Republic. This is a jewel in the middle of Europe with its historical, cultural and human melting pot. September 7th to 10th 2023.

”Photo Tour in Granada”—a week in Nicaragua for the adventures. We will explore the colonial city and its extraordinary countryside. October 23rd to 31st 2023.

”On the Tracks of Che Guevara”—ten days in eastern Bolivia. This is a great opportunity to discover one of the most beautiful countries in South America. October 23rd to 31st 2023.

Are you interested in developing your photographic skills? Do you like to travel? Do you want to make your photos tell a story in a much stronger vocabulary? Find your own expression? Develop your vision and become more creative? Any of these workshops would take your photography to the next level. I promise you, you will be in for an amazing experience. Click any of the links for more info.