This post is taken from my latest photo ponderings, Sideways, which I write every month or so. As you may you know, in this blog I usually write about creativity in general, using my experience as a photographer, but not limited to photography. Sideways is all about photography in which I offer nuggets of photo inspiration.

I am a people photographer by heart. As much as I photograph other subjects, it’s people that make me tick when I am out using my camera. For that very reason, I am a devoted documentary photographer.

A couple of weeks ago I attended a photo master class in Casablanca. It was taught by the renowned photographers Maggie Steber and Sara Terry. Both are routed in the documentary tradition; however, both with a strong poetic vision. This is why I attended their class; to encourage a more poetic approach in my photography, and leave some of the rational, linear and journalistic thinking behind. It’s a direction I have sought and tried to develop for a few years already.

What an experience the class was! Maggie and Sara were so good at pushing and encouraging, not only me, but everyone.

My assignment during the week was simply how does feel to be in Casablanca—or wherever I was. Of course, I took in and applied thoughts and focus points of other participants. Complex composition, for instance, photos with layers of depths, was much in discussions all the time.

But: how does it feel? That seems like an easy assignment. I almost always let my feelings guide my photography. Often, it’s some kind of attraction to people I decide to photograph. It’s about connecting to who or whatever I photograph. But feeling as a subject in and of itself, that is quite a different matter. How do you transfer feeling sad or melancholy or delighted into a photograph—in a place unknown to you?

Not easy. Not as topic on its own. Not to me.

Generally, photography is really about how it feels rather than what it looks like. It’s about seeing that even the mundane details, at home as in faraway places, can be extraordinary and full of feelings. When we get it right, they can feel like timeless gifts. I think of photographs of this kind as kisses: They exist in a brief ecstatic moment and then take on a life of their own.

Photography, at its best, is about moments—particularly when photographing people. It’s never about how it looks. When staying on the surface, and using easy digital effects to make our pictures pretty, we risk trivializing how we really experience our lives. Because, in the end, that is what we want to capture. Life as it unfolds—even when we photograph inanimate objects.

The unforgettable photograph isn’t the most technically proficient or the most “artistic” shot or the one with the “best” composition but the one that makes the deepest connection to the moment you are experiencing and the person you are photographing. It’s about your experience inside a moment.

This life of ours, whether we try to photograph it or not, is a string of moments, like notes in a song. So is a photo shoot, wherever you happen to photograph. You literally capture one moment after the next. Which moment will provide the unforgettable pictures isn’t much in your control. You can’t really see what your camera is capturing in the hundredth of a second the shutter is open. Often, you have no clue what your best photo is until you look at the series of moments playing back on your camera. Often, because that little screen on the camera doesn’t tell you much, the surprise may happen on the computer, hours or days later.

If you can’t see the moments, you can feel their flow, like feeling the flow of music. That feeling is essential to taking captivating photos; it’s as important as having a good eye. Ask yourself, “What makes these moments and these people extraordinary?” Ask that, rather than: “What’s the pose? How am I framing or composing?” And let your feelings steer you to the answer.

Alas, like I wrote, I like to compare taking photos to a kiss. Do you use your eyes when you kiss? Sometimes, maybe, but generally your eyes are closed and it is all about feeling. I try to photograph from the same place.

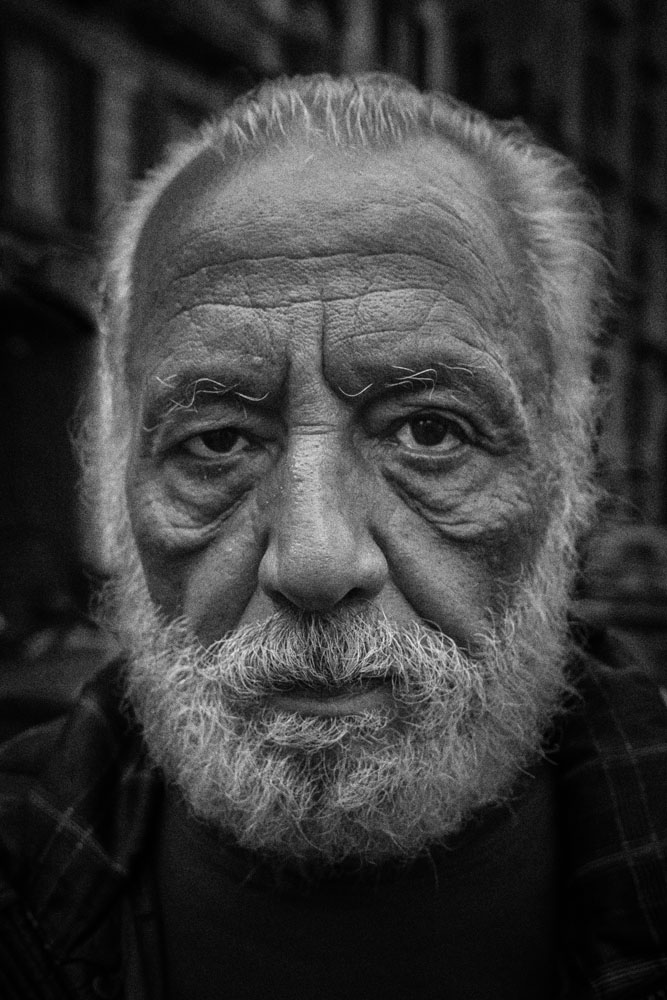

Take the photo above, captured in the medina, the old town, of Casablanca. I came across these two gentlemen enjoying a quiet moment and their tea together on a street corner. It would probably be wrong to say that it was love at first sight, but there was something serene and so universal about their repose. Asked if it was OK for them to be photographed, they agreed, and I lowered myself to their level and started to take a series of photographs of them. First, they looked into the camera and smiled. However, I was after an off-moment when they didn’t relate to my photographing them. So I kept shooting. At some point I, mostly unconsciously, registered a guy moving into the frame on the street around the corner, adding some depth to the situation. I shifted the camera a little to the left—and took a handful of more frames. The last frame is the one in which the moments fall in place, the two men in the foreground looking away, commenting on something behind my right, and the guy around the corner standing still for a moment.

It all happened in a fluid exchange, me feeling my way, more than seeing and consciously thinking.

So during the class, how did it go with photographing feelings as a subject of its one? Let me put it this way: It’s an ongoing project. And I am having a lot of fun—as frustrating as it can be.

Would you like to get motivating thoughts related to the act of photographing? Every once a month I write Sideways—nuggets of inspiration on photography. Sign up to receive Sideways in your email.

Photo Workshops and Tours Spring 2024

These are the photo workshops I and Blue Hour Photo Workshops plan for the coming spring.

“The Personal Expression”—a weekend in Bergen, Norway with focus on how to develop your personal, photographic expression. May 3rd to 5th 2024.

“On the Path of Cold War Memories”—a very special workshop exploring Berlin in a historic light. Go back in time to when there were two Germanies and two Berlins. May 12th to 17th 2024.