In the book “The Act of Creation” by the Hungarian author Arthur Koestler—first published back in 1964—he writes that there are three criteria of technique in artistic creation. Those are, according to him, originality, emphasis and economy.

Having those criteria in mind when we create, I believe would be useful to anyone of us who lunge into a creative endeavour. Not that we need to have a framework imposed on us when we create, but we can nevertheless benefit from keepings his criteria in mind.

With originality, Koestler refers to the unexpected, that which comes as a surprise. Personally, I am often reluctant to accentuate originality in and of itself. When we seek the original, we tend to become stall and contrived. We simply cannot deliberately invent originality, that is, sit down and cook up something completely new. The original comes to us by being ourselves, creating genuinely out of what feels right for each of us—whatever it is, we are creating.

The original comes to us when we don’t expect it. It suddenly appears from the subconscious after we have put work into a project and after a certain incubation time. Suddenly we see the connection that we have been searching for. It can happen when we sleep or when we go for a walk or when we do something that does not require intense thought activity. Because it is when we mentally relax that we give the subconscious an opportunity to find a solution.

According to Koestler, the original or the unexpected appears in the intersection between two apparently incompatible planes, dots that unexpectedly become connected. He uses the word bisociation, as a play on the word association, meaning linking up two different planes.

While originality thus is a product of an unconscious process, Koestler’s two other criteria are more related to a conscious approach—not that they cannot be unconsciously spurred.

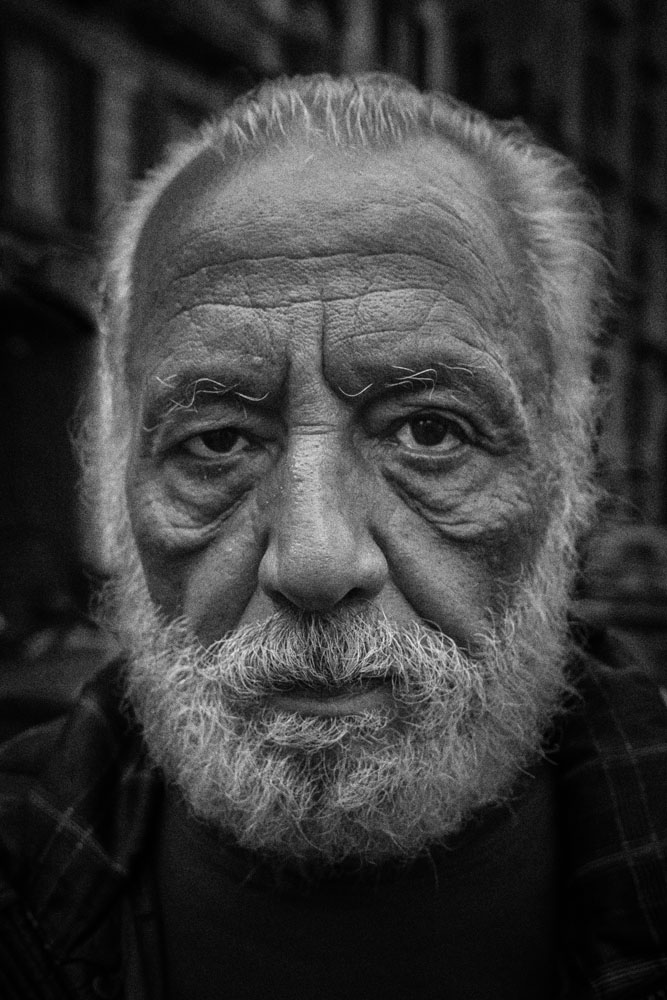

Emphasise we make happen through selection, exaggeration and simplification. For me as a photographer that means I want to include within the frame only those elements that tell the story I want to tell and leave out those that don’t add anything to the story. I put emphasise on the main object by making it bigger, focus the light on the object and let compositional lines direct the eye to it.

Using a suggestive approach is another way of emphasizing, according to Koestler an essential technique. Suggestions create suspense and facilitate the audience’s flow of associations along habit formed channels. Koestler points out that all non-essential elements should be omitted, even at the price of a certain sketchiness.

Taken together, this three factors, selection, exaggeration and simplification, provide the means of highlighting aspects of reality considered to be siginificant. However, Koestler points out that emphasis is not enough; it can defeat its own purpose. Ir must be compensated by the opposite quality: the exercise of economy, or, more precisely the technique of implication.

This authentic story about Picasso illustrated Koestler’s three criteria of technique in artistic creation:

An art dealer bought a canvas signed ‘Picasso’ and travelled all the way to Cannes to discover whether it was genuine. Picasso was working in his studio. He cast a single look at the canvas and said: “It’s a fake”.

A few months later the dealer bought another canvas signed ‘Picasso’. Again he travelled to Cannes and again Picasso, after a single glance, grunted: “It’s a fake”.

“But cher maître”, expostulated the dealer, “it so happens that I saw you with my own eyes working on this very picture several years ago”.

Picasso shrugged: “I often paints fake”.

The last sentence is both original, emphatic and implicit. Picasso doesn’t say: “Sometimes, like other painters, I do something second-rate, repetitive, an uninspired variation on a theme, which after a while looks to me as if somebody had imitated my technique. It is true that this somebody happened to be myself, but that makes no difference to the quality of the picture, which is no better than a fake; in fact you could all it that—an uninspired Picasso apeing the style of the true Picasso.”

None of this was said; all of it was implied.

Would you like to get motivating thoughts related to the act of photographing? Every once a month I write Sideways—nuggets of inspiration on photography. Sign up to receive Sideways in your email.

Photo Workshops and Tours Spring 2024

These are the photo workshops I and Blue Hour Photo Workshops plan for the coming spring.

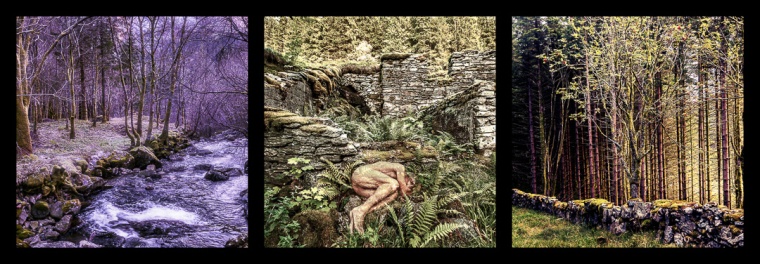

“The Personal Expression”—a weekend in Bergen, Norway with focus on how to develop your personal, photographic expression. May 3rd to 5th 2024.

“On the Path of Cold War Memories”—a very special workshop exploring Berlin in a historic light. Go back in time to when there were two Germanies and two Berlins. May 12th to 17th 2024.

Are you interested in developing your photographic skills? Do you like to travel? Do you want to make your photos tell a story in a much stronger vocabulary? Find your own expression? Develop your vision and become more creative? Any of these workshops would take your photography to the next level. I promise you, you will be in for an amazing experience. Click any of the links for more info.